Read our 2024 annual report

Knowledge Hub

Where there is a will there is a way: Reflections on the Rwandan genocide

Concern CEO, Dominic MacSorley, led Concern's response to the tragedy that unfolded in Rwanda 25 years ago. He shares his recollections of the devastating aftermath of the genocide and reflects on the lessons learned in order to prevent such atrocities from happening again.

No will to take action

Three months before the genocide in Rwanda, General Roméo Dallaire, Force Commander of the UN peacekeeping mission sent his now infamous "Genocide Fax" to United Nations headquarters in New York.

Recognising the rapid build-up of arms in the capital Kigali, Dalliere believed that if the UN peacekeepers were authorised to conduct raids on the arms stores, they could prevent a potential mass slaughter.

Understanding that he was pushing a decision that was not without risk, one that stretched the mandate of the UN mission, he added a final line, the only one written in his native French "Pea Ce que vex. Allon-y" (‘Where there is a will, there is a way. Let's go.’)

Nothing happened. Instructions from headquarters warned against "unanticipated repercussions" that could result from taking action. In New York it seemed there was neither the will, nor the way.

Over 800,000 people murdered

On the night of 6 April, 1994 the plane carrying Rwanda’s President Habyarimana was shot down and the genocide began. Brutally efficient, in less than 100 days, over 800,000 Tutsi, and Hutu moderates were murdered. A million people were internally displaced, two million fled to neighbouring countries, and 95,000 children were left orphaned. Rwanda was ravaged, the country was literally strewn with rotting corpses, all survivors physically damaged and psychologically traumatised.

The scale of the destruction and displacement was unprecedented. The brutality and enormity of the killings challenged us all on every level, striking at the core of our moral fibre, our humanity. We asked how this could happen and we vowed ‘Never Again'

Concern's largest ever regional humanitarian response

When I got the call from Jack Finucane to head up Concern’s emergency operations in Rwanda I had already been part of large humanitarian operations in places such Cambodia and Sudan. However Rwanda was on a different scale and, in my 36 years with Concern, nothing before or since has been as challenging as that time.

Death was everywhere. Violence hung in the air. The scale and complexity of establishing operations, already challenging, was massively compounded by the fact that nothing was functioning. The country had stopped. There was virtually no movement, no noise. Banks, businesses and markets were closed. In the first weeks Concern had to ship in its own food supplies and ironically among them were packets of Barry's tea that came from the same Rwandan tea plantations that now lay abandoned, the tea plants rotting in the fields.

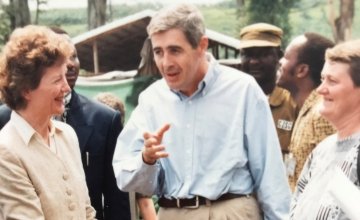

Across four countries – Rwanda, Burundi, Tanzania and Zaire (now Democratic Republic of Congo) – Concern mounted its largest ever regional humanitarian response. The response from Ireland was phenomenal. The health services released nurses that had previously worked with Concern. The Irish Defence Forces seconded logistics personnel and former Minister for Justice, Nora Owen, volunteered her time, spending three months in Kigali running support services for thousands of families returning home.

By June, Concern had over 1,000 national and international staff working to ensure that hundreds of thousands of survivors received emergency assistance – food, shelter, healthcare – and the practical support needed to begin to re-establish some sense of life and normality.

Overwhelming trauma

Urgency and the immediacy of responding to a humanitarian crisis is often an effective and sometimes necessary barrier to becoming overwhelmed by the scale and horror of the context you are working in. Yet there are moments that cause you to stop and force you to confront what you are dealing with.

I recall the day when a 12-year-old girl accompanied by her guardian came to the door of a house Concern was renting. It had been her home. She was the only survivor and now the legal owner of the house. She never spoke, she simply wanted to sit in her pink and yellow bedroom, the one with the posters of Mickey Mouse, still on the wall.

Extraordinary resilience, but recovery is not inevitable

Dwelling in the past is an important part of remembrance but Rwanda is not only a story of the gravest and most inhumane acts in recent history; it is also a story of recovery, resilience and the ability of humanity to overcome appalling atrocity.

It is a resilience, however, that should never, ever be tested. Resilience is not inexhaustible. And while Rwanda has been transformed, with one of the fastest economic growth rates in Africa, recovery for all is not inevitable.

That was painfully evident to me on a return visit a number of years ago. In a village, set deep in the hills of this beautiful country, I met the women who had successfully ‘graduated’ out of poverty to a more stable self-sustained future. Nine out of every ten participants in the Concern graduation programme were successful and now had a small business. However, I also wanted to also meet the women who did not make it.

I was introduced to 42-year-old woman who lived in shabby hut. Despondent and unwilling to make eye contact, her demeanour was in stark contrast to the other graduates. All her earnings went to supporting her husband still in prison for acts of genocide. Stigmatised by many in the community, her spirit has been crushed. Her ability to ever economically and socially recover was deeply uncertain. These are the stories you do not hear about but they are the realities in countries where the spectre of conflict takes generations to fully recede.

Aid is no substitute for peace

Humanitarian aid and development assistance has, and continues to be, a crucial building block of recovery and transformation. But it can never be a substitute for political will to prevent these situations from happening.

Just two months after the end of the genocide, a joint evaluation of the international response was conducted. The most damming findings were levelled at the UN Security Council, where conflicting political interests combined with a general lack of interest in a country that was considered to be of marginal strategic importance, resulted in no action.

There are certain times in history that have a defining resonance and meaning for us; they shape our sense of who we are, collectively and individually. Some, such as the Rwandan genocide, should haunt us forever and must never be forgotten. But remembrance cannot stop short at paying tribute to victims and survivors, it must drive action and compel us to do even more to stop the atrocities and gross human rights violations that are happening every day in Syria, the Central African Republic and other parts of the world.

Never again – An obligation to act

In the 25 years since Rwanda, some lessons have been learnt and we have witnessed faster, more comprehensive international responses to Darfur, Kosovo, Libya and the Kenya riots. However, these interventions have been only partially successful and there are many more failures than there are successes and the UN Security Council has been unforgivably ineffective in halting the mass atrocities in Syria.

As we mark the 25th anniversary, we must remember the danger of indifference and bear in mind, as the Genocide Convention compels us, that taking action to prevent atrocities is not a policy option; it is an international legal obligation of the highest order.

It is this, and only this, that can truly honour the dead of Rwanda and enable us to find the will and the way to fulfil our promise of “never again”.

*An edited version of this piece was published by the Sunday Business Post on April 14, 2019.